|

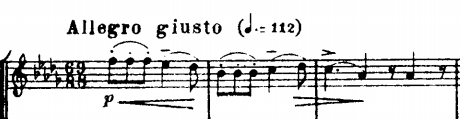

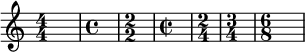

Time signature An example of a 3 4 time signature. The time signature indicates that there are three quarter notes (crotchets) per measure (bar). A time signature (also known as meter signature,[1] metre signature,[2] and measure signature)[3] is an indication in music notation that specifies how many note values of a particular type are contained in each measure (bar). The time signature indicates the meter of a musical movement at the bar level. In a music score the time signature appears as two stacked numerals, such as 4 Most time signatures are either simple (the note values are grouped in pairs, like 2  Basic time signatures: 4 4, also known as common time ( 2, alla breve, also known as cut time or cut-common time ( 4; 3 4; and 6 8 Time signature notationMost time signatures consist of two numerals, one stacked above the other:

For instance, 2 Symbolic signatures

By convention, two special symbols are sometimes used for 4

These symbols derive from mensural time signatures, described below. Frequently used time signaturesSimple versus compoundSimple meters are those whose upper number is 2, 3, or 4, sometimes described as duple meter, triple meter, and quadruple meter respectively. In compound meter, the note values specified by the bottom number are grouped into threes, and the upper number is a multiple of 3, such as 6, 9, or 12. The lower number is most commonly an 8 (an eighth-note or quaver): as in 9 Other upper numbers correspond to irregular meters. Beat and subdivisionMusical passages commonly feature a recurring pulse, or beat, usually in the range of 60–140 beats per minute. Depending on the tempo of the music, this beat may correspond to the note value specified by the time signature, or to a grouping of such note values. Most commonly, in simple time signatures, the beat is the same as the note value of the signature, but in compound signatures, the beat is usually a dotted note value corresponding to three of the signature's note values. Either way, the next lower note value shorter than the beat is called the subdivision. On occasion a bar may seem like one singular beat. For example, a fast waltz, notated in 3 Mathematically the time signatures of, e.g., 3

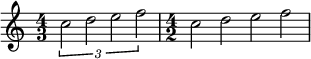

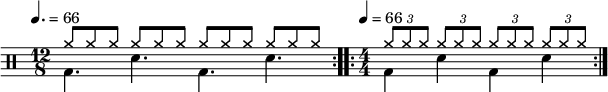

Other time signature rewritings are possible: most commonly a simple time-signature with triplets translates into a compound meter.

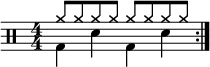

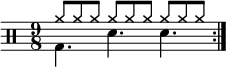

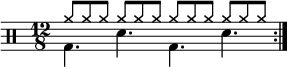

The choice of time signature in these cases is largely a matter of tradition. Particular time signatures are traditionally associated with different music styles—it would seem strange to notate a conventional rock song in 4 ExamplesIn the examples below, bold denotes the primary stress of the measure, and italics denote a secondary stress. Syllables such as "and" are frequently used for pulsing in between numbers. Simple: 3

Compound: Most often, 6

The table below shows the characteristics of the most frequently used time signatures.

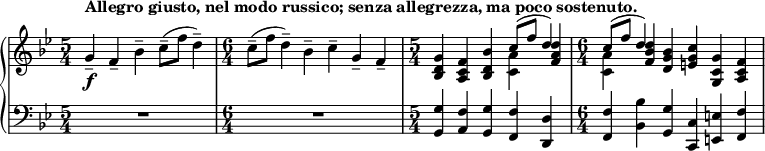

Tempo giustoWhile changing the bottom number and keeping the top number fixed only formally changes notation, without changing meaning – 3 This convention dates to the Baroque era, when tempo changes were indicated by changing time signature during the piece, rather than by using a single time signature and changing tempo marking.[5] Complex time signaturesSignatures that do not fit the usual simple or compound categories are called complex, asymmetric, irregular, unusual, or odd—though these are broad terms, and usually a more specific description is any meter which combines both simple and compound beats.[6][7] Irregular meters are common in some non-Western music, and in ancient Greek music such as the Delphic Hymns to Apollo, but the corresponding time signatures rarely appeared in formal written Western music until the 19th century. Early anomalous examples appeared in Spain between 1516 and 1520,[8] plus a small section in Handel's opera Orlando (1733). The third movement of Frédéric Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 1 (1828) is an early, but by no means the earliest, example of 5 Examples from 20th-century classical music include:

In the Western popular music tradition, unusual time signatures occur as well, with progressive rock in particular making frequent use of them. The use of shifting meters in The Beatles' "Strawberry Fields Forever" and the use of quintuple meter in their "Within You, Without You" are well-known examples,[10] as is Radiohead's "Paranoid Android" (includes 7 Paul Desmond's jazz composition "Take Five", in 5 However, such time signatures are only unusual in most Western music. Traditional music of the Balkans uses such meters extensively. Bulgarian dances, for example, include forms with 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 22, 25 and other numbers of beats per measure. These rhythms are notated as additive rhythms based on simple units, usually 2, 3 and 4 beats, though the notation fails to describe the metric "time bending" taking place, or compound meters. See Additive meters below. Some video samples are shown below.

Mixed metersWhile time signatures usually express a regular pattern of beat stresses continuing through a piece (or at least a section), sometimes composers change time signatures often enough to result in music with an extremely irregular rhythm. The time signature may switch so much that a piece may not be best described as being in one meter, but rather as having a switching mixed meter. In this case, the time signatures are an aid to the performers and not necessarily an indication of meter. The Promenade from Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) is a good example. The opening measures are shown below: Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring (1913) is famous for its "savage" rhythms. Five measures from "Sacrificial Dance" are shown below: In such cases, a convention that some composers follow (e.g., Olivier Messiaen, in his La Nativité du Seigneur and Quatuor pour la fin du temps) is to simply omit the time signature. Charles Ives's Concord Sonata has measure bars for select passages, but the majority of the work is unbarred. Some pieces have no time signature, as there is no discernible meter. This is sometimes known as free time. Sometimes one is provided (usually 4 If two time signatures alternate repeatedly, sometimes the two signatures are placed together at the beginning of the piece or section, as shown below:

Additive metersTo indicate more complex patterns of stresses, such as additive rhythms, more complex time signatures can be used. Additive meters have a pattern of beats that subdivide into smaller, irregular groups. Such meters are sometimes called imperfect, in contrast to perfect meters, in which the bar is first divided into equal units.[13] For example, the time signature 3+2+3

This kind of time signature is commonly used to notate folk and non-Western types of music. In classical music, Béla Bartók and Olivier Messiaen have used such time signatures in their works. The first movement of Maurice Ravel's Piano Trio in A Minor is written in 8 Romanian musicologist Constantin Brăiloiu had a special interest in compound time signatures, developed while studying the traditional music of certain regions in his country. While investigating the origins of such unusual meters, he learned that they were even more characteristic of the traditional music of neighboring peoples (e.g., the Bulgarians). He suggested that such timings can be regarded as compounds of simple two-beat and three-beat meters, where an accent falls on every first beat, even though, for example in Bulgarian music, beat lengths of 1, 2, 3, 4 are used in the metric description. In addition, when focused only on stressed beats, simple time signatures can count as beats in a slower, compound time. However, there are two different-length beats in this resulting compound time, a one half-again longer than the short beat (or conversely, the short beat is 2⁄3 the value of the long). This type of meter is called aksak (the Turkish word for "limping"), impeded, jolting, or shaking, and is described as an irregular bichronic rhythm. A certain amount of confusion for Western musicians is inevitable, since a measure they would likely regard as 7 Folk music may make use of metric time bends, so that the proportions of the performed metric beat time lengths differ from the exact proportions indicated by the metric. Depending on playing style of the same meter, the time bend can vary from non-existent to considerable; in the latter case, some musicologists may want to assign a different meter. For example, the Bulgarian tune "Eleno Mome" is written in one of three forms: (1) 7 = 2+2+1+2, (2) 13 = 4+4+2+3, or (3) 12 = 3+4+2+3, but an actual performance (e.g., "Eleno Mome"[15][original research?]) may be closer to 4+4+2+3.[clarification needed] The Macedonian 3+2+2+3+2 meter is even more complicated, with heavier time bends, and use of quadruples on the threes. The metric beat time proportions may vary with the speed that the tune is played. The Swedish Boda Polska (Polska from the parish Boda) has a typical elongated second beat. In Western classical music, metric time bend is used in the performance of the Viennese waltz. Most Western music uses metric ratios of 2:1, 3:1, or 4:1 (two-, three- or four-beat time signatures)—in other words, integer ratios that make all beats equal in time length. So, relative to that, 3:2 and 4:3 ratios correspond to very distinctive metric rhythm profiles. Complex accentuation occurs in Western music, but as syncopation rather than as part of the metric accentuation.[citation needed] Brăiloiu borrowed a term from Turkish medieval music theory: aksak. Such compound time signatures fall under the "aksak rhythm" category that he introduced along with a couple more that should describe the rhythm figures in traditional music.[16] The term Brăiloiu revived had moderate success worldwide, but in Eastern Europe it is still frequently used. However, aksak rhythm figures occur not only in a few European countries, but on all continents, featuring various combinations of the two and three sequences. The longest are in Bulgaria. The shortest aksak rhythm figures follow the five-beat timing, comprising a two and a three (or three and two). Some video samples are shown below.

A method to create meters of lengths of any length has been published in the Journal of Anaphoria Music Theory[17] and Xenharmonikon 16[18] using both those based on the Horograms of Erv Wilson and Viggo Brun's algorithm written by Kraig Grady. Irrational meters Example of an irrational 4 3 time signature: here there are four (4) third notes (3) per measure. A "third note" would be one third of a whole note, and thus is a half-note triplet. The second measure of 4 2 presents the same notes, so the 4 3 time signature serves to indicate the precise speed relationship between the notes in the two measures. Irrational time signatures (rarely, "non-dyadic time signatures") are used for so-called irrational bar lengths,[19] that have a denominator that is not a power of two (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, etc.). These are based on beats expressed in terms of fractions of full beats in the prevailing tempo—for example 3  The same example written using metric modulation instead of irrational time signatures. Three half notes in the first measure (making up a dotted whole note) are equal in duration to two half notes in the second (making up a whole note).  The same example written using a change in time signature. According to Brian Ferneyhough, metric modulation is "a somewhat distant analogy" to his own use of "irrational time signatures" as a sort of rhythmic dissonance.[19] It is disputed whether the use of these signatures makes metric relationships clearer or more obscure to the musician; it is always possible to write a passage using non-irrational signatures by specifying a relationship between some note length in the previous bar and some other in the succeeding one. Sometimes, successive metric relationships between bars are so convoluted that the pure use of irrational signatures would quickly render the notation extremely hard to penetrate. Good examples, written entirely in conventional signatures with the aid of between-bar specified metric relationships, occur a number of times in John Adams' opera Nixon in China (1987), where the sole use of irrational signatures would quickly produce massive numerators and denominators.[citation needed] Historically, this device has been prefigured wherever composers wrote tuplets. For example, a 2 A gradual process of diffusion into less rarefied musical circles seems underway.[citation needed] For example, John Pickard's Eden, commissioned for the 2005 finals of the National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain, contains bars of 3 Notationally, rather than using Cowell's elaborate series of notehead shapes, the same convention has been invoked as when normal tuplets are written; for example, one beat in 4 Some video samples are shown below. These video samples show two time signatures combined to make a polymeter, since 4

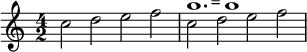

VariantsSome composers have used fractional beats: for example, the time signature 2+1⁄2  8 and 6 8 respectively) Music educator Carl Orff proposed replacing the lower number of the time signature with an actual note image, as shown at right. This system eliminates the need for compound time signatures, which are confusing to beginners. While this notation has not been adopted by music publishers generally (except in Orff's own compositions), it is used extensively in music education textbooks. Similarly, American composers George Crumb and Joseph Schwantner, among others, have used this system in many of their works. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze proposed this in his 1920 collection, Le Rythme, la musique et l'éducation.[21] Another possibility is to extend the barline where a time change is to take place above the top instrument's line in a score and to write the time signature there, and there only, saving the ink and effort that would have been spent writing it in each instrument's staff. Henryk Górecki's Beatus Vir is an example of this. Alternatively, music in a large score sometimes has time signatures written as very long, thin numbers covering the whole height of the score rather than replicating it on each staff; this is an aid to the conductor, who can see signature changes more easily. Early music usageMensural time signaturesIn the mensural notation of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries there are no bar lines, and the four basic mensuration signs Modern transcriptions often reduce note values 4:1, such that N.B.: In mensural notation actual note values depend not only on the prevailing mensuration, but on rules for imperfection and alteration, with ambiguous cases using a dot of separation, similar in appearance but not always in effect to the modern dot of augmentation. Proportions

Besides showing the organization of beats with musical meter, the mensuration signs discussed above have a second function, which is showing tempo relationships between one section to another, which modern notation can only specify with tuplets or metric modulations. This is a fraught subject, because the usage has varied with both time and place: Charles Hamm[23] was even able to establish a rough chronology of works based on three distinct usages of mensural signs over the career of Guillaume Dufay (1397(?) – 1474). By the end of the sixteenth century Thomas Morley was able to satirize the confusion in an imagined dialogue:

In general though, a slash or the numeral 2 shows a doubling of tempo, and paired numbers (either side by side or one atop another) show ratios instead of beats per measure over note value: in early music contexts 4 A few common signs are shown:[26]

In particular, when the sign Certain composers delighted in creating mensuration canons, "puzzle" compositions that were intentionally difficult to decipher.[27] Irregular bar

Irregular bars are a change in time signature normally for only one bar. Such a bar is most often a bar of 3 If a song is entirely in 4 Some popular examples include "Golden Brown" by The Stranglers (4 See also

References

Sources

Information related to Time signature |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia

![\new Staff <<

\new voice \relative c' {

\clef percussion

\time 3/4

\tempo 4 = 100

\stemDown \repeat volta 2 { g4 d' d }

\time 3/8

\tempo 8 = 100

\stemDown \repeat volta 2 { g,8 d' d }

}

\new voice \relative c'' {

\override NoteHead.style = #'cross

\stemUp \repeat volta 2 { a8[ a] a[ a] a[ a] }

\stemUp \repeat volta 2 { a16 a a a a a }

}

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/t/ht6hxyxpr9v3xb0cpjv683icswka64s/ht6hxyxp.png)

![\new Staff <<

\new voice \relative c' {

\clef percussion

\numericTimeSignature

\time 3/4

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 100

\stemDown \repeat volta 2 { g4 d' d }

}

\new voice \relative c'' {

\override NoteHead.style = #'cross

\stemUp \repeat volta 2 { a8[ a] a[ a] a[ a] }

}

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/9/s9u58cmgcnmemyzqn2af8injpsd1khj/s9u58cmg.png)

![\relative c {

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 144

\set Staff.midiInstrument = #"cello"

\clef bass

\key d \major

\time 5/4

fis4\mf(^\markup { \bold { Allegro con grazia } }

g) \tuplet 3/2 { a8(\< g a } b4 cis)\!

d( b) cis2.\>

a4(\mf b) \tuplet 3/2 { cis8(\< b cis } d4 e)\!

\clef tenor

fis(\f d) e2. \break

g4( fis) \tuplet 3/2 { e8( fis e } d4 cis)

fis8-. [ r16 g( ] fis8) [ r16 eis( ] fis2.)

fis4( e) \tuplet 3/2 { d8( e d } cis4) b\upbow(\<^\markup { \italic gliss. }

b'8)\ff\> [a( g) fis-. ] e-. [ es-.( d-. cis-. b-. bes-.) ]

a4\mf

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/8/b8fj1mi9xxb0txc1owjj4xyzjra58a5/b8fj1mi9.png)

![{ \new PianoStaff << \new Staff \relative c'' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"violin" \clef treble \tempo 8 = 126 \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #4 \time 3/16 r16 <d c a fis d>-! r16\fermata | \time 2/16 r <d c a fis d>-! \time 3/16 r <d c a fis d>8-! | r16 <d c a fis d>8-! | \time 2/8 <d c a fis>16-! <e c bes g>->-![ <cis b aes f>-! <c a fis ees>-!] } \new Staff \relative c { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"violin" \clef bass \time 3/16 d,16-! <bes'' ees,>^\f-! r\fermata | \time 2/16 <d,, d,>-! <bes'' ees,>-! | \time 3/16 d16-! <ees cis>8-! | r16 <ees cis>8-! | \time 2/8 d16^\sf-! <ees cis>-!->[ <d c>-! <d c>-!] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/h/qha58rrv2dvp8e20wcadsmov6ydccva/qha58rrv.png)